Field Study: To Invest or Not to Invest? The Question VCs Have about Digital Brands

I think we can all agree that digitally native vertical brands (DNVBs) have been hit as hard as any business model this year. Let’s take a walk down memory lane through the firestorm that was 2020: First, there was Casper’s pillowy IPO, then the FTC’s block of Harry’s deal, Brandless’s shutdown, and finally (ahem) COVID-19 and the election. There was no shortage of bad news casting a dark shadow over the Consumer sector and the so-called darlings of the e-commerce world, DNVBs.

I do not entirely disagree with the critical sentiment that was thrown at direct to consumer (DTC) back in February and March when the IPO market softened even further, nor do I think that digitally native brands are out of the woods after COVID sucker punched most supply chains and non-essential goods in the face.

Many VC’s, whether explicitly on Twitter or in the back breakout rooms of Zoom pitch days, have sworn off DNVBs. Many operators have warned of the flawed DTC playbook and of getting in bed with VCs. Much of the skepticism is valid. However, as someone who recently built and sold a DNVB, and who NOW as a new venture capitalist is tasked with looking at all things Consumer, I began to ask myself, “What do I make of all this?”

What Question Are We Really Asking Here?

First, I don’t think we collectively have asked the right question. The question is not “Should we as VCs invest in DNVBs anymore?”. Rather, I think the question is “WHEN should we invest in DNVBs given the current market environment?”

What are the possible outcomes? What multiples will the market bear? How much dilution will happen? How capital efficient will a brand need to be? What ownership thresholds need to be met? At which stage? What are the characteristics to look for in a particular business? And can we back any of this up with actual data?

(I also believe there is another question on when you should take VC money as a digital brand, but I will save that for another time).

As a former finance analyst (Fidelity what, what!), I began to wonder if I could back into a repeatable model or framework for my firm, Alpaca VC, one that would be useful for stress-testing possible investments into DNVBs over the next fund cycle. So in March, one of the first things I did on the job was to try to take both public and private data, alongside what I knew of portfolio construction math, and infuse that with founder and VC interviews, to create a fact-backed, scenario analysis of the top 60 DNVB exits over the last ten years. The goals were as follows:

- Identify insights from the data of the top 60 exited Digitally Native Vertical Brands (DNVBs).

- Understand what makes successful brands and founders. Understand the risks as well.

- Create a repeatable process and framework, based on these insights, to pressure test investing in brands out of a venture fund.

I have updated the figures and findings since I presented this internally to provide a point-in-time view of the market metrics as they exist today. So without further ado, here are the results of that work as of Q4 2020.

The DNVB Dataset

In an effort to create a data-driven view of the universe, we started with a very specific fact set. First, we narrowed our view to the top 60 exited DNVBs over the last decade. We then collected the following information about each firm, where available.

Data Collected:

- Years in business (before exit)

- Exit price

- Revenue at Exit

- Total Funding, including # of funding rounds

- Founder Makeup (gender, race, years working)

We crunched these numbers and found some interesting takeaways. We then set out to make sense of this data relative to what we know of VC portfolio construction and power law scenario analysis.

Of Note: This data is pulled from independent sources and publicly available data (including Crunchbase, CBInsights, Yahoo Finance). Big shoutout to Kofi Ampadu for providing me with his raw data collected and also shouts to our Associate, Eric Schoenbach, and our intern, Olivia Katcher, for helping wrangle this all in.

Additionally, this data doesn’t include some of the bigger DTC/DNVB successes that have yet to exit, notably Glossier, Warby Parker, Away, Him/Hers.

The Key Insights on DNVBs, by the Math

From a cursory look at the data, there were a few statistics that were relevant to the discussion around the exit itself, the raise, and the founders.

The Exit:

- Companies more often exited via M&A activity (53 of 58, or 92%) than did via an IPO.

- There were 5 unicorns in total; The Personal Care & Cosmetics category had the most unicorns with 3.

- On average, it took most companies almost 6 years to exit, however, the length of time it took a company to exit had no impact on exit value.

The Fundraise:

- Raising a lot of money did not necessarily mean a company’s exit value would be higher: 79% of the companies raised less than $50 million in total funding before exiting.

- Seed rounds consistently ranged between $1–2M but subsequent rounds varied by category.

- VCs and Angels were involved in 78% of investment deals across all categories.

The Founders:

- On average, companies with fewer than 3 co-founders had a better return on raised capital.

- A majority of the startups were founded by male founders (66%) or white founders (76%).

- On average, all-female founding teams generated a higher exit value than their male counterparts and all-white founding teams raised almost 5 times more (on average) capital than their non-white counterparts.

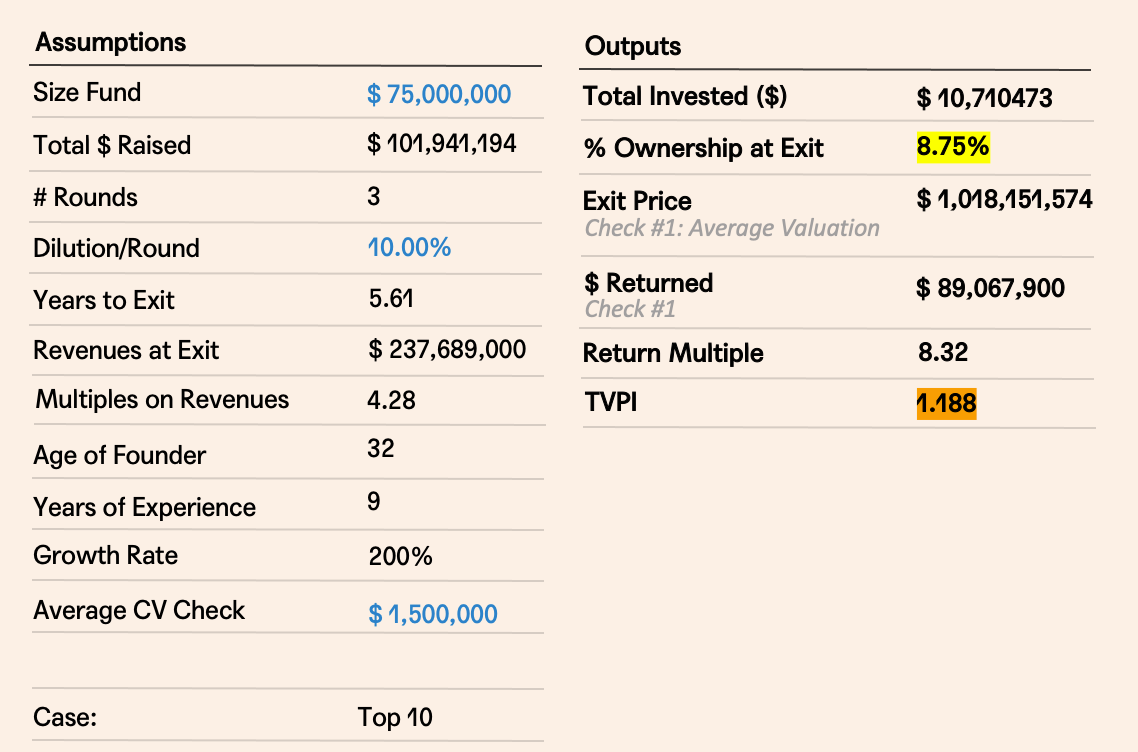

From this data set, I then ran the Top Ten company set and Median use case through a simple fund model to understand what the possible outcomes could be. To quickly break down the way that venture math works, let talk power laws. As a VC fund, and the way that power law curves work, a small % of a VC fund takes home a large % of venture returns. In practice, that means that VCs build their portfolio construction such that each deal that they assess should, in theory, return the fund.

So let’s say you have a $100M fund, that means that the VC wants to own enough of a particular startup such that when the startup exits, it can return $100M back to the fund. From running the Top Ten and Median cases through our model, and from speaking with overa dozen successfully exited founders, interesting takeaways emerged.

DNVBs are overcapitalized:

- There is a .82:1 ratio of capital raised to exit valuation, on average

- The highest exit valuations raised substantive funding ($102M, on average) though these investments still likely resulted in outsized Seed investor returns despite overcapitalization

- As we have already seen on the ground, abundant funding won’t likely continue in 2020–2021, so we need to believe a Seed company can get to scale without hundreds of millions of VC dollars

Seed valuations are too high:

- If exit multiples are at best 2.6–4.2, then Seed multiples need to reflect reality (this has started somewhat, but we still see overvalued brands, so shame on Pre-Seed, pre-revenue investors!)

- On average, we should expect companies to get to $55–350M in revenues in order to exit — and model exit scenarios off that potential (i.e., not $1B)

Ownership for DNVBs at Seed is paramount:

- Given that exit multiples and revenues are compressed (4.2X on $237M at the high end), owning substantially more of a Seed round is the primary way to ensure an outsized return

Size of fund matters for relevant outcomes:

- As a $37M fund (our fund II), the top end of DNVB exits presents interesting, fund-returning results; whereby picking a winner remains the goal

- As our fund size grows over $40M, it becomes harder — if we assume typical ownership — to return the fund and so the viability of finding a fund returner becomes harder

Path to profitability matters as does patient capital:

- Brands that did not experience a significant write down were profitable — or were close

- 5–6 years to exit means building brands takes time and capital needs to be patient

So When Should We Invest?

We thought it would be important to create a repeatable framework through which to assess brands moving forward. We then took the insights we found and developed two analysis tools:

- A DNVB Investing Tool to evaluate seed-stage opportunities against the 60 benchmarked companies and to understand what Alpaca should evaluate in terms of seed size, valuation, growth rate, dilution, and expected returns.

- An enhanced 19 Factor Matrix to incorporate key considerations for digital brands, specifically, as we diligence.

This framework allows us to easily pressure test check size, valuation, growth, ownership, dilution and also Goal Seek to understand what we would need to believe to return the fund.

We also came up with a clear diligence checklist to consider, beyond our 19 factor diligence matrix we use to assess all deals. If we are confident in the startup’s ability to satisfy these conditions, or alternatively are comfortable accepting the risks, IN ADDITION to our DNVB Investment Tool modeling + 19 Factor Matrix, we should consider investing.

What’s Next for DNVBs?

I’d like to now take a moment to provide my musings on where I think digital brands are headed and provide my perspective for brands and other co-investors reading this article. I believe we are starting to see what the new normal is for digital brands over the next ten years. There is a new playbook. What worked in 2010 will not work in 2020.

As Web Smith said, “The DTC era experienced a decade of grow-by-any-means marketing and often inefficient operations masked by excessive venture capital. As private companies, this can last as long as rounds can be raised. But they’re at the frontier now.”

DTC is Dead (as a term, anyway).

In the beginning (pre-2007), direct to consumer had the allure of higher margins and higher ROAS. But we all know that over the last few years, online advertising arbitrage has all but disappeared and brands cannot sustain $500 CACs at scale. As Eurie Kim said to me on the phone, “DTC is not a P&L advantage anymore.” Omni-channel is the new normal. Truly scalable brands need to figure out wholesale and retail, and figure it out well. 84% of transactions still occur offline, and the pace of brand growth will not outpace the growth of digital. We only need to look at the top ten exits quoted above to see that most of them had an omni-channel strategy by point of exit (Casper in Target and West Elm plus owned retail; Dirty Lemon in Walmart, Soho House and every fast casual restaurant south of Houston; Olly in Target).

Additionally, I’d also posit it’s no longer direct-to-consumer, but direct-to-community. As arbitrage has dried up across Google, Facebook and Amazon (who capture 70% of all digital ad spend, according to eMarketer), the winners will inevitably leverage the inherent networking effects of its community, which is hopefully and simultaneously niche, global, and in desperate need of their solution.

Profits over Prodigious Growth.

I actually don’t feel the need to justify this section too vehemently. We’ve seen that growing at all costs doesn’t work and that CAC and unit economics eventually catch up to a brand no matter how much funding it has raised. As Scott Galloway infamously wrote back in January, “The economics work better if #Casper sent you a mattress for free, stuffed with $300.” I believe we will see a return to shockingly boring fundamental unit economics, and that brands must figure out how to scale quickly yet efficiently. Enter my next point…

Hello, Debt

Because VCs have held the mic for such a long time, many entrepreneurs have understood equity financing to be the premier source of capital. The dirty secret of DNVBs is that debt is a key driver of the business — Bow & Drape (my brand), Rent the Runway, Everlane, Mizzen + Maine, and many others all raised debt alongside their equity to smooth out their cash flow cycles. Most founders I interact with have a hard time navigating debt, which is unsurprising as sources are varied and terms and covenants can be incredibly restrictive. However, I would advocate that it’s a critical part of any inventory-based business and it also gets easier with wholesale as a part of the mix (see earlier point about DTC being dead). Elizabeth Yin wrote an interesting piece on financing options that serves as a good primer for any young brand.

The Rollup, or Holdco, Approach

This may be controversial, but I don’t believe there will be another billion dollar digital mono-brand IPO-ing in the next ten years. Because barriers to create a new brand are lower than ever before (think all the resources at our fingertips: Shopify, Quickbooks, Slack, Alibaba, Instagram, TikTok, Amazon), brands globally can access more fragmented customer pockets and sustain themselves as smaller, more diverse businesses. In the wake of this trend toward brand and customer atomization, there will be more rollups — operating companies that spin up or purchase existing smaller brands (sub $100M) and try to accrete firm value from the amalgamation of the parts. That is not to say this model has its own challenges, including managing multiple customer communities, supply chains, and disparate brand cultures, but it’s an interesting exit opportunity for growing DNVBs. There have been some interesting new entrants into this fray, including Pattern Brands, WIN Brands, Juxtapose, and Forward Foods, all of which embrace the premium mediocre, domestic cozy aesthetic of Millennial and Gen z brand marketing.

The Affinity Marketplace

As more and more, small-ish global brands come into existence, I believe there will be an outcropping of what I call Affinity Marketplaces, or clearinghouses for brands with a very similar community-driven audience. Think Etsy on Steroids — hyper-targeted, global reach, micro-sellers. We’ve already begun to see the outcropping of some of these, whether it’s buying sustainably, buying LGBTQ+, buying Black, buying local. Brands will follow the CPG movement, where the DNVB is to Sir Kensington as the Affinity Marketplace is to Thrive Market or Imperfect Foods (portfolio company hype-beast). Brands should find arbitrage here wherever possible.

**********************************************

I hope this analysis is useful for fellow venture capitalists grappling with how to assess brands moving forward and provides a framework through which to analyze them. Equally, I hope this analysis sheds some light for digital brands on the challenges VCs face in saying “yes” to DNVBs (beyond the already hard task of getting to a “yes” from a VC). Know that investing is cyclical, and we are at the beginning of a new epoch for brands around the globe.

Sources and Helpful Articles I liked:

https://marker.medium.com/why-all-the-warby-parker-clones-are-now-imploding-44bfcc70a00c

https://builtin.com/e-commerce/dtc-dnvb-brand-growth

Disclaimer: Alpaca VC Investment Management LLC is a registered investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Information presented is for informational purposes only and does not intend to make an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of any securities. Alpaca VC’s website and its associated links offer news, commentary, and generalized research, not personalized investment advice. Nothing on this website should be interpreted to state or imply that past performance is an indication of future performance. All investments involve risk and unless otherwise stated, are not guaranteed. Be sure to consult with a tax professional before implementing any investment strategy. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Statements may include statements made by Alpaca VC portfolio company executives. The portfolio company executive has not received compensation for the above statement and this statement is solely his opinion and representative of his experience with Alpaca VC. Other portfolio company executives may not necessarily share the same view. An executive in an Alpaca VC portfolio company may have an incentive to make a statement that portrays Alpaca VC in a positive light as a result of the executive’s ongoing relationship with Alpaca VC and any influence that Alpaca VC may have or had over the governance of the portfolio company and the compensation of its executives. It should not be assumed that Alpaca VC’s investment in the referenced portfolio company has been or will ultimately be profitable.

COPYRIGHT © 2025 ALPACA VC INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT LLC – ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. All logo rights reserved to their respective companies.